Chasing The Tail Versus Riding The Walrus

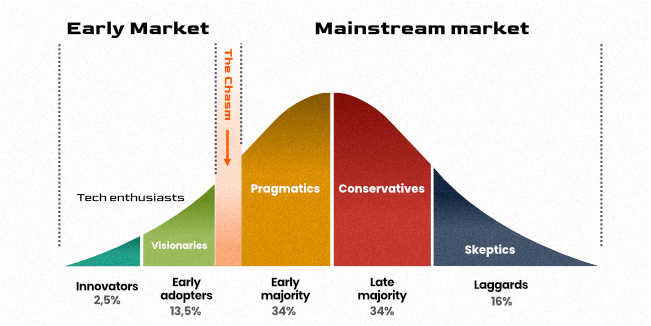

As someone who has had a leg in both finance and technology over the course of the second phase of their career, I think about this chart a lot. This is the Technology Adoption Curve, a broadly generalized distribution of the uptake of a seminal piece of technology that eventually becomes a ubiquitous part of every day life. While it is generally applied to technological advancements (cars, televisions, cell phones…electric cars, etc.), it can also be applied more broadly to any field where adoption comes on slow, gets a niche following, and then either dies on the vine or finds a Cambrian explosion of interest to push it into the mainstream.

Take cryptocurrency, for instance. Bitcoin has existed since late 2008s, with Satoshi Nakamoto’s paper on the currency being followed by the creation of the coin shortly thereafter. Those first few years saw bitcoin as nothing more than a passing interest for a few hardcore crypto tech folk, with early bitcoin transactions being used for tips, pizza, and other relatively benign payments. Bitcoin itself didn’t reach the chasm until 2012, when it started to receive some more notice in wider tech blogs, mostly due to BTC crossing the $1,000 threshold and the exchange Mt. Gox and its shift from Magic The Gathering to bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. This is when I was first heard about it: suffering from a non-quant mind at the time and a case of FOMO, I bought $100 of BTC, rode Mr. Bones’ Wild Ride for a bit, and then sold for a tidy profit of $10. If that (and the subsequent bottoming out of BTC price) wasn’t where bitcoin crossed the chasm, then 2017’s price run definitely was. This run was bolstered by the quasi-magical promise of the blockchain and web3 as the savior of the internet, leading to the Big Players to finally take it seriously. By that point, those innovators and early adopters were either cashing out or kicking themselves.

I wanted to mention crypto because it serves as a bridge between tech and finance, and finance is another realm in which this curve plays out. However, given the glacial speed at which technological innovation occurs in finance, we will not be applying this curve to that specific portion of the field. No, this curve can also be applied to investment strategies or even the markets themselves in the form of a narrative adoption curve. So much of strategy and movement in the markets works off the back of information scarcity. Hedge fund strategies that work well when starting out falter when AUM rises too high or the broader market adds the strategy to its information set and starts to chip away at its alpha. Bunches of people gushing over Value or Growth or Momentum or etc. at any given moment tend to indicate that we’re at or near the apex of that strategy’s bull run. The nightly news mentions a market bull or bear run? It’s probably time to get out. There’s an apocryphal story about JFK’s father realizing he needed to get out of the stock market right before the Crash of 1929 because his shoeshiner was offering him unsolicited stock advice. When you’re on the right side of the curve, it’s time to start looking for the starting tail of innovators at the beginning the next big narrative curve. Be careful though: you can’t know if that curve will be the Next Big Thing, or if you’re going to end up falling into the chasm.

Think I’m being a bit too overblown? Look at the recent stock market: uncertainty due to war, inflation, supply chains, and a post-pandemic flight back to a normalcy that might not be possible anymore had led to a lot of doomsayers coming out and predicting a recession. And they may be right! But the right time to have adequately prepped for this scenario is not when the S&P 500 drops 3% on a Friday, it was before this even started to occur. Attempting to emotionally invest your way out of a downturn is a surefire way to make sure you lose both now and in the future when the market starts its climb back up (which, again, will start happening long before any broad news outlet or narrative emerges). So really, there’s only two options here: constantly be hunting down the right path forward at a success rate that outpaces your losses from the failures…or find something that won’t ever generate the kind of unbridled enthusiasm, emotion, or excitement that an adoption curve does.

I think it’s pretty clear to most of my friends and family that Futurama might be my favorite show of all-time. Hell, I literally played on a Futurama-themed Ultimate team! I was Morbo! Some of the episodes of the show would have fake commercials from the year 3000+, one of which was a fast food chain hyping up its 100% fresh-squeezed walrus juice. This comes during the culmination of a brouhaha over the fast food chain’s last big product, so it’s pretty blatant that said fast food chain is attempting to distance itself from the previous product by offering up some brand new invention as an attempt to get lightning to strike twice. Setting aside the clearly unappealing nature of juice from any sort of animal, I always gravitated to this joke because of how much the ad is missing its mark, and how absolutely blatant the juxtaposition between trying to be cool and hip and “with it” and the product which cannot in any way be described as such.

I’ve worked in advertising for over half a decade at this point, and I can safely assume that 90% of ad content does not move the needle one way or the other beyond getting the brand name and its products/services out into the ether. The other 10% is probably a 2:8 split between legitimately good ads (hello Budweiser “Wassup” and Terry Tate: Office Linebacker) and legitimately terrible ads (Quinzos Spongmonkeys, the infamous Peloton ad, anything by Buick or Toyota) that have a discernible impact on brand performance beyond the mere placement of a generic replacement ad. The real trick with ads isn’t with the ads themselves: it’s with getting the right people to see your ad, getting them interested enough to actively click/seek out more information, and then make the next step into acquiring your product/service/etc. Everyone focuses on the first two, but the final step is the keystone in the entire process. A shitty product can only be glossed over and/or mislead for only so long before the whole house of cards comes falling down. A solid, well-made, and useful product will eventually make its way through…it may not be from the inventor or the first N companies that try it, but use tends to win out in the end. Granted, this might be harder to do with today’s VC mindset of fast and infinite growth instead of a more-natural uptake of something, but these things tend to work out in some shape or form.

So…between the adoption curve and walrus juice, what exactly am I trying to get at here? Simple: avoid fads. Find investment strategies that are straightforward, transparent, and so unbelievably unsexy that they’ll never succumb to a narrative adoption curve because they’re too boring and undramatic to fit into one. Get rich quick schemes work, but only for a small percentage of those involved, typically the innovators of the narrative and a couple lucky few who fall into the right timing for it, both of whom might have accomplished this through illegal means. On the other hand, index funds and ETFs tend to be a long, drawn-out process for their creators to fund, market, get investors, and ultimately make profitable. No one is getting into ETFs to get rich quick…and that’s one of the best things about them and other long-term strategies. Getting rich slowly tends to be one of the few paths that benefits both the creators and the customers. Hype is Icarian, and outside of luck, slow and steady is the only way to win the investing race.